Note: Who knew there’d be such TI news and drama the day after I posted my blog! Anyways, definitely looking to share my thoughts on the maybe-real Codex 3, but waiting for things to settle down before posting my hot takes.

If there has ever been a Twilight Imperium game that did not feature accusations of “winslaying” I have yet to witness it.

In fact, winslaying (and its close cousin winmaking) are so often thrown around that both are approaching the meaningless limbo of words such as literally and factoid.1 But, if you seek to win Twilight Imperium at any level, it is important to understand the various forms of logic (or lack thereof) that can govern late-game play, particularly the forms of winslaying that might manifest.

Let me begin by quickly saying what this article is not. It is not an attempt to dissuade anyone of their view of winslaying, or a persuasive defense of my own views. Instead, I hope to humbly provide a shared language that can be used to describe “win-slay” archetypes, and provide a few suggestions for how to negotiate with each type.

Philosophy 101; a Quick Detour

Before we begin to discuss the details of each type, I think one question underpins a lot of conflict over winslaying: is the act-omission distinction true? A staple of Philosophy 101 courses, the act-omission distinction posits that acting to bring about a result is not ethically the the same as omitting to act when that same result is likely to occur anyways.

tl;dr pushing someone into traffic is murder, but letting someone get hit by a car when you could’ve rescued them isn’t your fault (or at least not as bad as murder)

For an example from TI, consider the following:

It is a three-player game, where the Naalu and the Jol-Nar both sit at 9 points. They’ve both passed, have no secret objectives in hand and are planning to score an unstoppable tech objective (i.e. 2 in 2 colors). The third player, the L1z1x, has a massive fleet in range of both home systems. Unfortunately, they sit at a meager 5 points and only have one tactic token left.

With no plausible path to victory, and no way to stop both their opponents, should the L1z1x take the Naalu home system? To winslay the Naalu is to winmake the Jol-Nar, but to omit from acting is to winmake the Naalu. Neither truly helps the L1z1x, but is one more permissible than the other?

Obviously, the scenario is unusually this clean-cut. Paths to victory are usually unclear, far from guaranteed, and typically you have several players in a position to take action, not just one. But the fundamental question remains:

Is refusing to block a win the same as handing a player the win?

I think understanding how your table answers that question will get you 75% of the way to understanding your fellow players

The Flavors of Winslaying

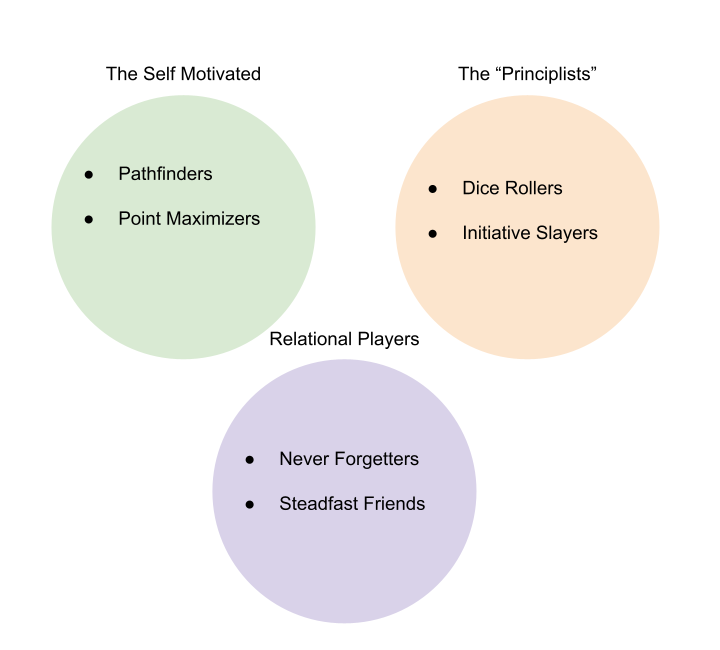

I think there are three main archetypes of winslay philosophy, each with a few variations within them.

The Self-Motivated

The first group is perhaps the most intuitive group: the self-motivated. These players will only seek to winslay another player if it furthers their own goals in some way. However, I think there is an important distinction between two types of self-motivated players.

Point-maximizers have a simple goal in mind: score as many points as possible. If winslaying the leader lets them score more points (either through objectives or prolonging the game) they are happy to help.

Pathfinders are those who will only winslay if they have a conceivable path to victory. They will only act to winslay the leader (and thus prolong the game) if there’s a realistic plan in their mind for how to win.

While these might seem identical, there are a few key differences. To a pathfinder, a loss is a loss, regardless of score. But a point-maximizer would rather with 7 points than with 5. To that end, a pathfinder type player is unlikely to help winslay if they’re far behind the table in points, while a point-maximizer will happily slay the leader the game if it means getting one last public or secret in before someone else wins anyways.

These players are perhaps the easiest to negotiate with. Offer to help them score points directly and they’ll likely consider accepting your deal. Both are also typically amenable to so-called Magi’s Gambits.2 Keep initiative/speaker order in mind for both players. Even without path to 10 VP, a point-maximizer is incentivized to stop those ahead of them in scoring order (so they can score one last time) but may care less about picking sides between two inevitable winners. Meanwhile, a pathfinder is typically quite interested in any deal that involves improving their speaker position or may ask other players to harm their own positions (such as giving up trade goods needed for an objective) in order to level the playing field. They often don’t need to have a good path, just a plausible one.

The Relational Players

These players are the most likely to pick an ally and stick with them in the end game. The only distinction is whether they’re motivated out of love or hate.

Steadfast Friends will often decline to winslay a player with whom they had good relations all game, and may even go so far as to help or winmake them.

Never Forgetters, well, they never forget. They remember that time you threatened them with Reactor Meltdown round two, and frankly, they don’t believe you should win because of that. Essentially, rather than picking their friends to win, a never forgetter will work tirelessly to slay their enemy.

My main advice for handling these players is to get ahead of it in the early game. It is unlikely anything you can do in the late game will change their existing impressions of you. But if you know you are playing with one of them early, you can attempt to help them when you can and avoid unnecessary provocations. If, however, you are in the late game with one of these players: if you can’t rely on your own good behavior, try and highlight the bad behavior of your opponents.

“If you winslay me, then Muaat is just gonna win, and he super-nova’d your whole fleet last round! All I did was not refresh you” is typically much more persuasive than “Wow, you’re still salty about that?”

My final note is that this is probably the only category that people will masquerade as in the early and mid-game. On the extreme end someone might promise you their support once you get to 9 points, and on the more common end people will threaten to throw their game by bogging you both down in a forever war if you attack them. Identifying the true believers from the pretenders is hard but critical work.

The “Principlists”

A principle is defined as “a fundamental truth or belief” and while these players may have one of those, that doesn’t mean it is based in logic.

The Initiative Slayers have a singular goal: stop whoever is in-line to win first. It doesn’t matter if they’re last in initiative and the entire table is at 9, they have a rule and they stick to it. This typically means beginning with the speaker, and moving clockwise until each player has either been acquitted of having a path to victory, or been sufficiently winslayed.

The Dice Rollers on the other hand, have a much more abstract goal: have fun and roll dice! This where you’ll see pointless suicide attempts at taking Mecatol, or massive fleets clashing over useless planets.

Negotiating with either of these players is… tough, to say the least. Initiative Slayers can at least sometimes be persuaded that someone else may win first (usually via action phase secrets or Mecatol points) or that you don’t have a path. Dice Rollers however, typically march to the beat of their own drum. My best advice is to try and encourage them to do something epic that doesn’t interfere too much with those more focused on winning (“hey, if you don’t move here, I’ll send a fleet here and we can have it be epic”) or to appeal to their sense of drama by proposing a gambit of some kind. For example I once saw a player agree to forgo both PDS fire, sustain damage, and Magen Defense Grid in order to make a combat “a high-stakes coin flip” in order to receive concessions from another player.

A Selfish Call For Empathy

One of my great friends (and mortal TI enemies) Rasmus often will ask players in Round 5 a simple question:

“What is your winslay philosophy?”

This may seem obvious, but the act of listening first, then negotiating second, is far more effective in getting the table to gang up on the point leader than leading with “Well obviously we need to stop X player because of Y right?” and being flabbergasted when they don’t agree. This game is fun, but it can also be tense and full of emotions. No one likes being winslayed, and even winslaying leaves a bad taste in some people’s mouth. But hopefully with a little empathy for the players at your table you can understand the events of a final round of Twilight Imperium as the rational action of players with differing philosophies rather than being bewildered and frustrated when the whole table doesn’t agree with you. I also think you’ll probably win more games that way too.

Addendum: “I Swear I Can’t Score My Secret”

There is one last distinction between players that falls less neatly into ideological buckets: how does your table assess (unrevealed)3 unscored secrets?

To talk about this I’d like to coin a new acronym: E.S.S. (Expected Secret Scorability). This encompasses both how likely it is a secret can be scored, and how quickly (i.e. is it Action Phase). For example, imagine a player at 9 points with no secrets in hand, and a player at 7 points with 3 secrets in hand. Who is the bigger threat? Well it depends on your view of E.S.S. and I think there’s good arguments on both sides.

Well it depends on how you evaluate their E.S.S. There is no “right answer” to this. Things like board state, number of scored secrets, and secret draw tempo all may influence a evaluation of a player’s E.S.S. But understanding how your table and meta evaluates this is crucial to planning your path to victory (and thwarting your opponents).

See here for the short history how factoid went from meaning “false statement that seems true” to essentially being a synonym for fact

For those unfamiliar a Magi’s Gambit is when 2 players agree to some deal that increases the odds of one of them winning, often but not always involving helping each other score your secret objectives. A classic example is a combat between two players at 9, one holding “Win a combat in an anomaly” and the other holding “Win a combat agains the player in the lead.” If they agree to an evenly matched fight in an asteroid field, one of them is guaranteed to win.

My thoughts on revealing secrets are too long for this post, but keep an eye out for a future post about them

You don't score in speaker order tho. You score in initiative

Love this analysis, and it is good advice for how to navigate different player's end-game expectations. After reading it, I've found myself to be a very relational player. I will actively make endgame deals that favor someone who was a good neighbor to me all game, or even to another underdog that I find myself rooting for. I even have a strong bias towards players who chose a weaker faction out of respect. On the other hand, if someone was manipulative during the game or is winning because their faction carried them, I will be strongly inclined to enact my view of justice on them. If I've had a relationally neutral game, I will make end-game moves that simply add to the drama of the space opera. Let's roll the dice!